An Economic (Human Capital) Theory of Stagnant U.S Nuclear Power Generation Innovation

The Lasting Effect of Chernobyl and Three Mile Island

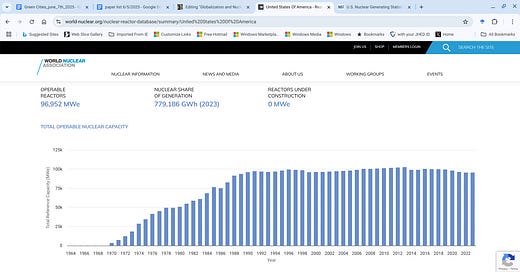

In 1971, 2.4% of U.S electricity was generated by nuclear power plants. By 1980, this % had grown to 11% (data source). By 1992, this % had increased to 20% and over the last 33 years it has barely changed. How do we explain this puzzle? Here is graph of the absolute level of nuclear power plant capacity over the last 65 years.

This is an interesting time series! Sharp growth occurs in the 1970s and 1980s and then the trend is completely flat for 35 years. This is a time when we have been deeply concerned about the greenhouse gas emissions and local PM2.5 air pollution created by coal fired and natural gas power plants.

Why have nuclear power plants floundered in recent decades? We know that the answer in large part revolves around liability land land use issues focused on disposing of nuclear waste and the memories of Three Mile Island (1979) and Chernobyl (1986) Disasters.

New Point

I claim that if the Three Mile Island the Chernobyl Disasters had not occurred, that the U.S would have continued to build more nuclear power plants and the expectation that more nuclear power plants would be built would have encouraged more Universities to invest more in nuclear power education.

The Three Mile Island shock occurred in 1979 and the Chernobyl shock occurred in 1986. People born around the year 1960 and after were less likely to want to train in nuclear engineering and skills focused on nuclear power careers because they anticipated that the demand for nuclear power plants would decline. Universities responded by investing less in these programs. As less talent enters a PHD field, it dries up.

An ugly Catch-22 arose here. The horrible irony here is that nuclear power generation becomes riskier as less talent enters the field! The stagnant nuclear power sector arose because of a human capital gap. Talent stopped flowing into this sector because young people anticipated that the sector had no future after the 1979 and 1986 disasters.

This claim can be rigorously tested using patent data in the nuclear sector before and after the shocks and by studying major university (such as MIT) investment in nuclear engineering over time. As older faculty retired, were they replaced?

A Counter Argument

Now, I recognize that in a globalized economy that trained French and Japanese people could migrate to the U.S to work on our power plants. An open empirical question relates to whether there are enough of these individuals to staff our facilities.

The Relevant Economics?

Labor economists study the choice of careers and choice under uncertainty. All of us are young once. We choose what sector to specialize in. At one point in the 1970s, nuclear power was a sexy up and coming field in the U.S. Shocks occurred and the party ended. The U.S would have had lower air pollution and GHG levels had we stayed on course.

Did we “over react” to the shocks?

I have published two articles that are related to how such events shift politics.

Kahn, Matthew E. "Environmental disasters as risk regulation catalysts? The role of Bhopal, Chernobyl, Exxon Valdez, Love Canal, and Three Mile Island in shaping US environmental law." Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 35 (2007): 17-43.

Costa, Dora L., and Matthew E. Kahn. "Death and the media: infectious disease reporting during the health transition." Economica 84, no. 335 (2017): 393-416.

In my 2007 paper, I document that progressive policy makers in the Congress respond to salient shocks by proposing more radical legislation. These policy makers recognize that there is a short window (perhaps 6 months) when the New York Times and other leading media outlets are covering a story. This gives them a short window to push for more radical legislation. Who has the “upper hand” in the pressure group fight after a disaster?

My paper with Dora establishes that the media focuses on “bad news”. The median reader/voter engages with this slant and this must affect the voter’s worldview.

Once nuclear power was established as “scary stuff”, it had trouble countering this perception. The horrible irony here is that this causes a “brain drain” making the sector more stagnant and riskier today as the Trump Administration tries to jump start it.

It is interesting to ponder whether we can just import blueprints from Japan and France on how to build safer power plants.

We will never know what nuclear power path we would be on today if our leading engineering universities had consistently invested in training and researching nuclear power. The U.S has the world’s best Universities. If our scientists and students substitute away from a given issue such as nuclear power, then there is a global loss in knowledge.

I recognize that I have focused on the high end of nuclear power plant design and innovation. There is also the day to day operations at a power plant. What skills are needed to excel there? How quickly can these be learned? Some facts are posted here.

To wrap up, did Chernobyl trigger an ugly self-fulfilling prophesy? Nuclear power is risky because we think nuclear power is risky and thus we disinvested and this caused young people and their universities to substitute away?

UPDATE: Here are a few more facts about nuclear power plants. The first figure shows that almost no new nuclear power plants were built between 1990 and 2017 in the USA.

Very interesting theory but, as you point out, it seems to operate only through the operation and maintenance staff - which is comprised of a small share of nuclear engineers. I am not sure it matters quantitatively for the evolution of nuclear in the US. A more important consequence of nuclear curtailment seems to be the scale effects. The US is the largest nuclear producer in the world. If its nuclear share increased, it would certainly have an effect on innovation - but world wide

https://reeceashdown.substack.com/p/iran-at-the-edge-of-the-atom?r=5qrbeg