DOGE Will Increase Government Efficiency

Why Do Economists Have Trouble Benchmarking Public Sector Efficiency?

How do economists benchmark whether the federal government is becoming more productive over time? How do we rank Ohio’s government versus California’s government regarding service delivery per dollar spent?

New York City allocated $10.8 billion for the City’s Police Department in 2024. It allocated $39.9 billion for its Department of Education. Was this money well spent? What do the words “well spent” mean? If Elon Musk’s DOGE were brought to NYC to search for waste in these two budgets, how much $ would Mr. Musk propose to be cut from their respective budgets? What would be lost from such cuts? Who would feel the pain from these cuts?

The same questions can be asked about Federal Department budget cuts. The U.S. military may face an 8% funding cut. How do such cuts affect our nation’s security?

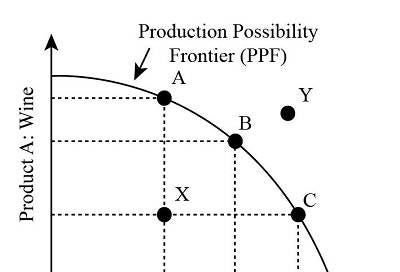

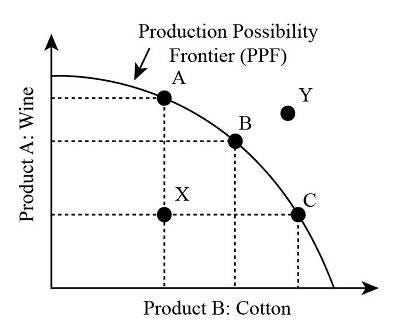

In undergraduate Econ 101, we teach our students about tradeoffs made by consumers and firms. In both cases, students encounter diagrams like this.

In this diagram, a consumer wants to consume as much wine and cotton as possible. Given her resources and production technologies, she must choose between points X, A, B, and C. She cannot reach point Y. Point Y lies outside her production possibilities frontier. Point X lies inside her production possibilities frontier. Points A, B, and C are feasible and lie on her PPF. Which one of these she chooses depends on her preferences. If she prefers wine over cotton, she is likelier to select point A over point C.

Elon Musk and DOGE argue that governments spend our money, often choosing a point such as “X.” They inefficiently use government revenue. Mr. Musk is saying that if this government money were returned to the people, we would spend it more wisely because we would have the right incentives to spend our money on our priorities.

Opponents of DOGE argue that much government spending is spent on public goods such as basic research and helping poor people and that individuals will free-ride and tend not to support such initiatives. In this brief substack, I will not discuss this issue further.

Instead, I want to focus on efficiency. What are the government's incentives to spend money efficiently? Every Economics Student is taught that consumers and firms have private incentives to spend $ efficiently because they lose out if they waste money. Does the same logic hold for Governments? No. Governments pursue multiple objectives simultaneously, and there are cases where the government is more likely to achieve one of its goals if it spends more money than it needs to. I will return to this point below.

First, what does the word “efficient” mean?

In Econ 101, we define “efficient” as the “Bang per $ buck spent” is equalized across all spending categories. For example, it is Saturday Night, and Matt is going out with his friends. That night, he had budgeted $50 for dinner that he would spend on beer and pizza. Beers are $5 each at the restaurant, and slices of pizza are $10 each. Matt can afford the following pairs (10 beers and no pizza, eight beers and one slice, six beers and two slices, four beers and three slices, two beers and four slices, zero beers and five slices). Matt will ask himself, “Which of these five combinations makes me the happiest?” Suppose the answer is four beers and three slices. He has allocated his $ so that any other affordable bundle of pizza and beer makes him less happy. He has equated his “bang per $ buck spent” between spending on pizza and beer.

In the case of government allocating $ across tasks, such as the police versus education, or within a budget category, such as the Pentagon prioritizing the Army versus the Navy, there is no single decision maker. Large committees with different goals, expectations, and priorities determine the budget allocation. For example, the NYC Department of Education head may care more about educating children and paying public teachers more. This Head of the Education department would say that her goal is to deliver an “excellent education for all children,” but what do those words mean?

The Education Department, with a 39 billion dollar budget, has tremendous discretion in choosing the allocation of $ across parts of the budget. This government budget allocation committee will likely overpay for inputs such as teachers, school custodians, and student bus drivers. These high-paying jobs help create middle-class jobs with low unemployment risk. At the same time, by overpaying for these services, the Education Department is more likely to choose a point like “X” in the diagram above.

NYC’s people cannot easily monitor the Department of Education’s budget. They do not know the “what if” concerning how much cheaper it would be to supply the same quality education if the schools were privately managed. The privately managed entity would be a profit maximizer with a financial incentive to run the organization at the lowest possible cost, subject to attracting customers.

In my academic research, I explored this subject. In 2017, we studied how U.S. urban Transit Agencies differ concerning their average cost of moving a public transit bus a mile. Moving a bus a mile requires a bus, a driver, and gasoline. This fixed input (Leontief) production structure made it easier to study the agency’s efficient cost than in other cases featuring a more complex production process such that there are more input substitution possibilities.

Our paper suggests significant privatization gains for other government functions, ranging from garbage pickup to schooling. Before DOGE, people knew little about how Federal, State, and Local officials spent public funds. They could not easily consider whether the private sector could supply basic services at lower cost and higher quality. DOGE is expanding people’s imagination concerning the proper scope of the State versus the private sector.

I encourage DOGE to listen to government agency appeals when they argue they are using taxpayer $ efficiently. I claim that this dynamic process of forcing government agencies to compete to keep revenue would give them more substantial incentives to use their $ efficiently. Until recently, they have not been held accountable for how they have spent $. Using “other people’s money” has given agency heads the power to use public funds without being held accountable. This is a bad incentive structure. In this sense, DOGE’s sunshine will increase the efficiency of the Federal, State, and Local Governments.

If the Government were to become more efficient, taxpayers would be charged less in taxes for achieving the same level of services. As the tax rate declines, fewer voters will oppose government expenditures! In this sense, progressives gain from government efficiency progress!

If DOGE didn’t exist, government agencies would continue to have private information about their budget allocation activities. This creates bad incentives for pursuing the “public good.” Those who know they have discretion will be more likely to pursue their goals. If DOGE’s activities lead to a more transparent discussion of what different government agencies do all day, this will strengthen our democracy and trust in government.

Update; DOGE’s early efforts have taught me that economists haven’t done enough research on sunshine laws applied to government. Yes, researchers have access to contract databases and we have access to the U.S Census of Governments and we have access to payroll data. Even with these data, economists are not able to reconstruct the tradeoffs that government department heads face. We need such information to test the core efficiency hypothesis. What is the cheapest way to achieve a given goal? Did the agency head choose that option? If not, “why not”? When do government officials have an incentive to pursue cost minimization? When do they pursue multiple goals at the same time such that their agency’s average costs are much higher? If DOGE didn’t exist, the “rational ignorance” hypothesis posits that no individual voter has an incentive to research these issues. The free rider problem predicts that government officials will continue to have wide latitude concerning how they spend taxpayer funds. Many people oppose DOGE. My question for this group is simply; “How will improved governance occur?”

DOGE represents a credible threat to incumbent interest groups in government. They will reoptimize and the efficiency of their organizations will improve. This doesn’t mean that DOGE is perfect. I recognize that I haven’t discussed what are DOGE’s “real motives”. My point in this short Substack is to highlight how a credible threat brings about behavioral change.

Matthew: Clearly DOGE is highly controversial in substantial part because it appears to have authority delegated by the President to implement immediately its views regarding what actions should be taken to reduce Federal Government expenditures. I vigorously challenge that authority. I believe it is unlawful.

I have no problem with creating a DOGE-type ADVISORY committee/commission whose views must be considered by all of the government entities affected AND by the House and Senate committees with jurisdiction over such agencies and their expenditures.

I, also, believe that a properly organized DOGE-type advisory-only entity would EITHER retain the human capital necessary to evaluate for each Federal government entity the criteria Congress has established for the spending by such entity OR absent such hiring the DOGE-type entity would make recommendations that consider only efficiency AND defer to the government entities and relevant Congressional committees consideration of whether and how efficiency might properly/should be considered relative to the Congressionally established program implementation criteria.

Respectfully,

Clem Dinsmore

Wilmington, DE

clem.dinsmore@gmail.com

"slices of pizza are $10 each" -- ouch! Looks like a good place for budget cutting to start!