In my urban and environmental economics classes, I gross out my undergraduates as I discuss urban dog poop in Italy. This 2014 New York Times article fascinates me.

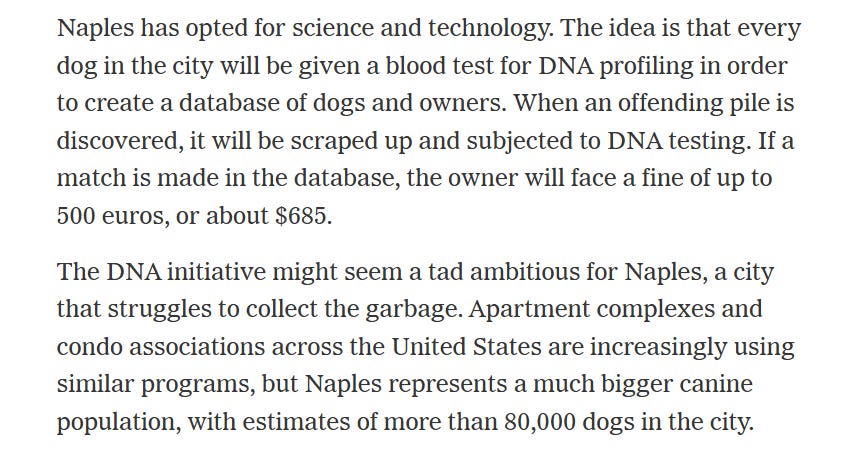

Naples recognized that its public property was being degraded. To address this Tragedy of the Commons problem, it required that dog owners register their dogs and provide a DNA sample from their dogs. This sample solved an accountability problem. When the City finds dog poop on the streets, it matches that DNA to its database and when it finds the owner, it fines the owner! Returning to Gary Becker’s work on crime and punishment, deterrence is a function of the probability of being caught engaging in illegal activity (p) and the fine if caught ($F). The expected value of the punishment equals p* F, and if this product is high enough, then lazy people start to protect common property!

What are the lessons for Oakland, California and its huge garbage problem?

The New York Times recently reported;

The simple economics of illegal urban dumping focuses on expected benefits and expected costs. The private benefits of dumping garbage include convenience and avoiding out-of-pocket costs associated with proper disposal. Similar to the Italy Dog Poop case, these private costs of illegal dumping would soar if there were a credible deterrence system, perhaps including drones and surveillance, and taking photos of license plates of people who drive up and dump stuff in the common areas of the city.

If more urban Oakland land were privatized, this challenge would also lessen.

In my work on urban economics, I am quite interested in public/private complementarities. For example, if an urban park is located in a high crime area then the park is a disamenity because it attracts gang and drug activity and homes located nearby will sell for a discount. Conversely, if a park is pretty and safe; homes nearby will sell for a price premium.

Albouy, David, Peter Christensen, and Ignacio Sarmiento-Barbieri. “Unlocking amenities: Estimating public good complementarity.” Journal of Public Economics 182 (2020): 104110.

Zheng, Siqi, and Matthew E. Kahn. “Does government investment in local public goods spur gentrification? Evidence from Beijing.” Real Estate Economics 41, no. 1 (2013): 1-28.

In the case of Oakland, it could be a highly amenity-rich city, boasting its local beauty and proximity to Berkeley and San Francisco. Street safety and garbage lower the area’s desirability, reducing investment in new businesses and new real estate construction. Yes, the area avoids the dreaded “gentrification,” and rents stay low, which benefits the incumbent poor; however, at the same time, the area under-performs.

Economists need to do a better job of explaining how local economic growth leads to improvements in the standard of living for all. If housing regulations in cities such as Oakland could be repealed, then the issue of improving local quality of life and driving up local rents would be partially alleviated.

Do the Oakland Poor prefer a setting with low rents and lots of garbage to living in a Greener City? If the Mayor is responsive to this group of voters (if they vote), then this begins to sketch out how a stable political equilibrium emerges, characterized by a low level of local public goods being supplied and rejecting the creative solution to the urban Tragedy of the Commons Problem in Naples, Italy.

If this Substack interests you, read my 2025 Free to Choose in the American City free book, available here.

Progressives do not care about crime. let alone mass shootings - unless racism can be used. https://torrancestephensphd.substack.com/p/crickets

Very interesting to learn how to penalties and why putting penalties is essential for standard of living