Elon Musk expects Tesla’s workers to be in the office five days a week. Most Wall Street bosses agree with Mr. Musk. Citi is one Wall Street exception. This firm encourages some WFH. Is it a coincidence that the CEO of Citi is a woman? Jane Fraser continues to endorse WFH for her firm’s employees. She argues that the WFH job perk gives her firm a hiring advantage as it competes for talent.

Back in 2019, workers went to work five days a week. Such face-to-face daily meetings facilitated learning, mentoring, and worker monitoring. Under these “rules of the game”, a stubborn gender gap in earnings has persisted. Even for the select set of graduates of elite MBA programs, a gender gap in earnings emerges a few years after graduation.

A paper co-authored by the Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin and published in 2010 documents that even among top MBA graduates, some women choose to drop out of the labor force just a few years after graduating to pursue raising a family.

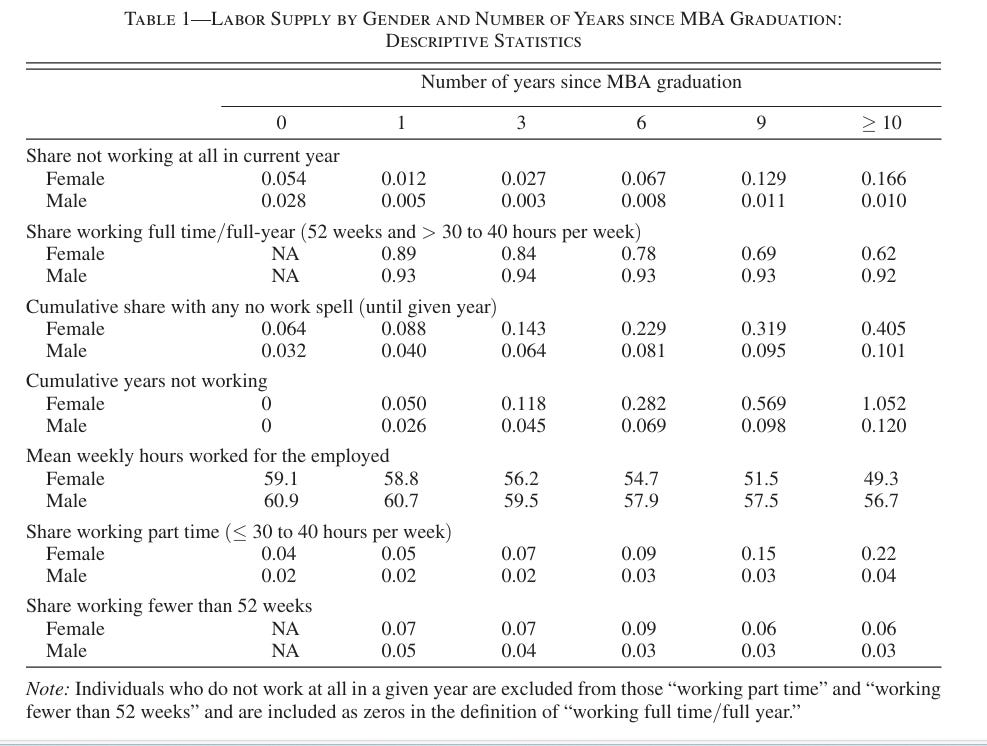

Here are two pieces of information from the Bertrand et. al. paper published in 2010.

These data provide facts about University of Chicago MBA graduates who completed the program between 1990 and 2006. Suppose that the typical graduate is age 27. The averages reported above show that at graduate, there is little evidence of a gender gap. Nine years after graduation (see the 2nd column from the right), when the typical MBA graduate is age 36, 93% of men are working full time while only 69% of women are working full time. Ten years after graduation, a 30 percentage point gap in labor force participation has emerged!

Now, let’s turn to earnings.

This graph features the log of annual earnings on the y-axis and years since graduation from the MBA program on the x-axis. Note that the median earnings gender gap is tiny immediately after graduation but as the years pass, the gender gap emerges for graduates from the same elite program. Note the 90th percentile gap as Superstar men are earning much more than Superstar women and the 90th percentile of the female earnings distribution is surprisingly flat from 9 to 13 years after one finishes the University of Chicago MBA program.

The gender gap in employment rates and earnings over the years 1990 to 2006 was likely to be caused by workplace dynamics. Female graduates of the University of Chicago MBA program invested a large tuition payment and two years of training to enroll in this elite program. Despite this fact, just a decade after taking this training many had chosen to opt out of working entirely. Perhaps some of them experienced discrimination at the firm where they were working but there are many other firms one can work for.

In the recent past, why did many very talented women opt out of working? Going forward will WFH attenuate the tradeoffs they faced during a time when WFH/hybrid work was not a viable option?

In my 2022 Going Remote book, I offered an urban economics explanation for the female opt out puzzle focused on commuting and preparing to spend the day at the office. If one is required to commute and prepare 5 days a week, then this acts as a disincentive to work. Thus, the rise of hybrid/WFH work that requires workers to be in the office 2 or 3 days a week helps to close the gender gap as more mothers could “have it all” by raising a family and working in a hybrid/WFH set up.

My logic is based on a famous paper that is now 43 years old. In 1981, John Cogan from Hoover wrote an important economics paper that offers an urban economics explanation for the persistent gender gap.

While Dr. Cogan wrote his paper, 40 years before our society’s collective WFH experiment, his study anticipated the worldview that Citi’s CEO embraces. Put simply, there is a fixed cost that one must pay each day in order to work at an office.

He examined how commuting and the time spent preparing to work at the office discourages women from participating in the workforce. For example, if a mother wants to work 5 hours a day but spends a total of 2.5 hours on dressing and commuting roundtrip (which amounts to 12.5 hours per week), this fixed cost of 2.5 hours reduces her likelihood of working. However, if she could work from home five days a week, this fixed cost would be eliminated entirely. If she worked from home just two days a week, her fixed cost would drop to 7.5 hours, making her more inclined to work.

There are many educated mothers who want to work while simultaneously achieving their household goals but they face binding time constraints. There are only 24 hours in the day. Given where they live and given low commuting speeds (with the risk of disrupted congested roads creating some inconvenient monster commutes on bad weather days and when accidents occurs), it isn’t worth it to them to commute to work 5 days a week.

In my 2022 Going Remote book, I argue that the rise of hybrid/WFH helps to solve this problem.

My logic;

Firms (such as Citi) that offer hybrid/WFH will attract more applicants to hire and will be more likely to retain such workers at a lower annual earnings.

Hybrid/WFH will increase mother’s hours worked and overall labor force participation

In the pre-WFH world, bosses anticipated that many young women would opt out and leave the firm in order to raise families. Many of these bosses invested less time mentoring such workers because they anticipated that they were leaving. This mentoring gap contributed to some of these women choose to leave. This is a Bad Nash Equilibrium (think of Russell Crowe in the John Nash movie; Beautiful Mind). To repeat my point, an ugly self-fulfilling prophesy played out.

In our new hybrid/WFH world, bosses at firms such as Citi now anticipate that young women will be more likely to stay with the firm and work Hybrid/WFH when their children are young. This dynamic creates more within firm career continuity. The Citi bosses anticipate that young women will keep working and thus the bosses invest more time mentoring these young women. The net effect is new opportunities for women to pursue their career goals and to close the gender gaps identified in the data I presented above. Thus, I predict that WFH will play a role in shrinking the gender gap documented by Bertrand et. al in the paper I sketched above.

Let me wrap up by pointing out my ongoing work with Emma Harrington on this topic.

You can read our draft here. The short answer to our paper’s question is “Yes!”.

At Hoover, Nick Bloom and Steven Davis lead a major empirical research project investigating the costs and benefits for firms, workers and society of utilizing WFH. My own research interest here focuses on the implications of persistent WFH for urban quality of life. You can read more about my WFH and cities work here.

To conclude, I am fascinated by this emerging competition between firms that require RTO versus those firms such as Citi that allow hybrid/WFH to continue. Tradeoffs emerge. Citi will face some co-ordination, learning and mentoring challenges because some workers are not around for face to face meetings. At the same time, WFH firms such as Citi will attract a larger pool of workers. Mr. Musk questions whether these WFH workers are shirking. This is an important question that merits more analysis of how accountability is achieved when workers are granted more privacy that allows them to balance family and work goals.

The occupancy rate of commercial buildings will perhaps be more important in determining the federal government’s WFH policies. The WH occupant is a real estate developer and hates empty spaces. He will listen carefully to the anguished cries of the lenders and the developers alike.